“I think they’re going to be really excited about it!”

That confident declaration came from a senior leader who had spent months designing a future-state vision for his team which would result in sweeping change. The statement was well-intentioned—and perhaps even accurate for some. But it lingered with me because it underscored a common trap in organizational transformation: the oversimplification of emotional reactions to change. Leaders often put people into one of two camps – supporters or resisters – rather than acknowledging human complexity and examining what may be driving their reactions.

And yet, time and again, I’ve found that resistance is usually a proxy for something more nuanced: unacknowledged loss.

When “Routine Tasks” Are Anything But

One experience that has always stayed with me took place during a hospital care team redesign. The project involved integrating nursing assistants into workflows to take on basic tasks, allowing registered nurses to focus on more complex patient needs. It was, on paper, a win-win: improved efficiency and a better use of nursing expertise. The “WIIFM” (“What’s in it for me?”) message for nurses seemed cut and dried. Leaders assumed nurses would be excited about the change.

But when I checked in with one of the leaders, her face told a different story. “I just don’t understand why this group of nurses is so resistant to change,” she said.

She was especially puzzled by their apparent unwillingness to give up the task of bathing patients. To the leadership team, bathing patients was a time-consuming, routine task. To the nurses, it was something else entirely. Brief interviews revealed that this task allowed them to pause, connect with patients on a deeply human level, and quietly assess their condition—skin texture, body language, energy level. It was a moment of presence and purpose that reinforced their identity as compassionate, competent caregivers. And in their own words, it made them better at their job.

While it may be tempting to dismiss resistance as simply irrational or inconvenient, this example illustrates the deeper drivers at play and the opportunity to pause and understand.

The nurses weren’t resisting the logic of the change—they were reacting to the loss of something meaningful. And perhaps most importantly, that meaning was invisible to those who hadn’t lived it.

We can’t view someone else’s experience of change through our own lens and expect to see the same picture. Personal experience isn’t up for debate; it simply is, and it matters.

Change Isn’t Just About Logic—It’s Also About Loss

Too often, leaders and change agents focus solely on the business rationale and the “WIIFM” talking points to drive employee engagement. Those are important, but not sufficient. They may secure surface-level buy-in to the end goal, but fail to address basic motivation to show up and engage with the change day-to-day.

To understand the difference, one needn’t look farther than a classic human struggle: the desire for health and fitness. Many people crave the outcome (they’re “bought-in”)—but resist the emotion-laden reality of giving up things that matter to them. It might be the luxury of rest exchanged for an early morning jog, the ease of carefree meals replaced by the mental load of healthy planning, or the comfort of spontaneity traded for the discipline of routine. The intended gain is clear, but the loss—though seemingly small—is personal and real.

Change, even when logically beneficial, often disrupts the routines, comforts, or self-concepts that anchor our sense of stability.

The bottom line? People don’t just make reflective, rational choices when responding to change. Much of our behavior stems from reflexive, emotional responses, whether we realize it or not—especially when change threatens our sense of identity, purpose, or connection. Knowing the difference and navigating the nuances is crucial to effective change leadership.

Balancing the Equation: The Role of Gain

While loss often takes center stage in conversations about change, it’s only one side of the equation. Loss tends to be more immediate and emotionally charged which — especially combined with the human negativity bias — makes it easier to spot. Gains, in contrast, are often delayed, distributed unevenly, or obscured by early uncertainty. To lead change effectively, we need to understand how both loss and gain coexist—and how they show up differently across individuals and over time.

Let’s look at an example.

A quality team I worked with transitioned from data-heavy backroom work to collaborative, real-time consulting with product and service teams. Two team members had strikingly different experiences:

- Mei, a quiet but highly valued data visualization expert, had built her identity around deep technical competence. The new expectations—presenting insights, working cross-functionally—felt like a threat to that identity. She worried she’d lose status, confidence, and the sense of accomplishment that came from being the go-to person for technical mastery.

- Ravi, on the other hand, had grown bored with data work. His strength had always been storytelling and real-time problem-solving. Though his past attempts to connect data to field realities weren’t always appreciated, this shift gave him the chance to shine—and to feel reenergized and relevant.

Neither of them was wrong. Each experienced both loss and gain—just in different ways, on different timelines.

In fact, it is common for the same employee to experience both loss and gain within a single change. For example, I may gain status with a promotion but reflexively struggle with the shifting peer relationships that once grounded my sense of connection. I may feel inspired to rise to a new challenge but simultaneously experience a loss of competence when I realize that my influencing skills are lacking compared to my technical skills, which are now less relevant. Am I “resisting” my promotion if I find myself repeatedly drawn back into technical details? Perhaps – but that label offers little value. It oversimplifies the experience and ignores the nuanced factors that might actually be addressed through thoughtful support.

Effective change leadership requires more than managing loss. It means identifying the diverse and sometimes delayed ways that gains emerge—and helping people recognize and connect to them.

The True Nature of Resistance

Labeling people as “resistant” flattens their experience and limits your options as a leader. If you treat resistance as something to overcome rather than understand, you miss the opportunity to address the underlying emotion, value, or identity in question.

More importantly, you miss the opportunity to design better interventions: ones that support real adoption, not just compliance. And you lose the chance to effectively leverage gains—whether they emerge organically from the change or can be cultivated through targeted leadership action.

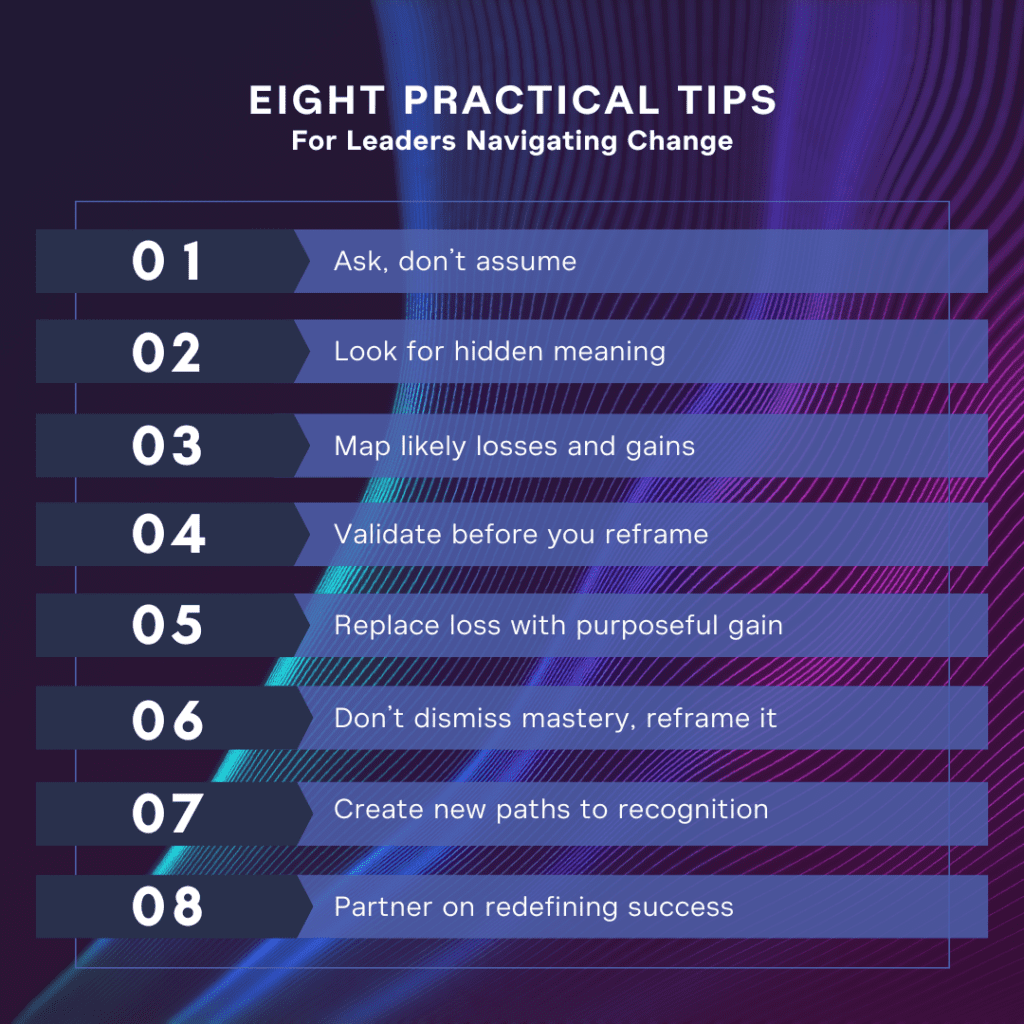

Practical Tips for Leaders Navigating Change

1. Ask, don’t assume. Instead of labeling someone as “resistant,” get curious. Ask open-ended questions like:

- “What does this change mean for you personally?”

- “What concerns do you have about how your work will change?”

- “Is there something you feel we’re losing that matters to you?”

- “What part of your identity do you want to carry forward?”

- “What will help you feel valuable and successful in your new role?”

2. Look for meaning beneath the surface. If someone seems stuck on a “minor” task or process, explore what it symbolizes. Is it tied to their sense of purpose, competence, or connection? What looks small to you might carry real emotional weight for them.

3. Map likely losses and gains. Before rolling out changes, consider:

- What might people feel they’re losing in this shift?

- What aspects of someone’s identity or status could feel diminished?

- What sources of confidence or meaning might no longer be available?

- What might they gain—now or over time?

- How might this change better align with someone’s strengths, interests or values?

Use this to anticipate emotional reactions and to plan support.

4. Validate before you reframe. If someone shares a concern, don’t rush to fix it or sell the upside. Start with:

- “That makes sense.”

- “I can see why that would be hard.”

Validation builds trust. Reframing only lands when someone feels seen and heard.

5. Replace loss with purposeful gain. Don’t stop at acknowledging loss: intentionally design ways to help people regain confidence, identity, or influence in a new form. Ask, “What might this person need to feel equally valuable, confident, or connected in the new environment?” Then create experiences, roles, or coaching that build intentional pathways from loss to gain.

6. Reframe mastery, don’t dismiss it. When someone’s established strengths or identity are no longer front and center, reframe their expertise in a way that fits the new environment. Help them see how those same skills still matter—just in a different form, role, or context. For example, a technical expert may no longer be hands-on but can now be positioned as a strategic interpreter or integrator of that expertise.

7. Create new paths to recognition. If a change disrupts how someone earned credibility or status, make space for new forms of contribution to be seen and celebrated. Publicly recognize wins – even if success looks different than it used to.

8. Partner on redefining success. Co-create development paths that connect evolving roles to future growth. Give people agency in shaping what success looks like in the new world, not just acceptance of what’s changing.

Acknowledging Loss

When leaders acknowledge loss, they demonstrate empathy. When they help people discover or design new sources of gain—confidence, connection, recognition—they foster growth. In the messy middle of transformation, those gains don’t always arrive on time or look like we expected. That’s why great change leadership isn’t just about delivering logic or reinforcing outcomes. It’s about guiding people through the emotional terrain, helping them reconnect to meaning, and reflecting back the progress they may not yet see in themselves. When we do this well, we don’t just drive adoption—we help people write a new story of who they are becoming in the process.